UWF Uses 3-D Technology To Recreate History

Pensacola – Hours after the discovery of a new species of human ancestor was announced, Dr. Kristina Killgrove was able to put replicas of bones from the landmark archaeological find in the hands of her students.

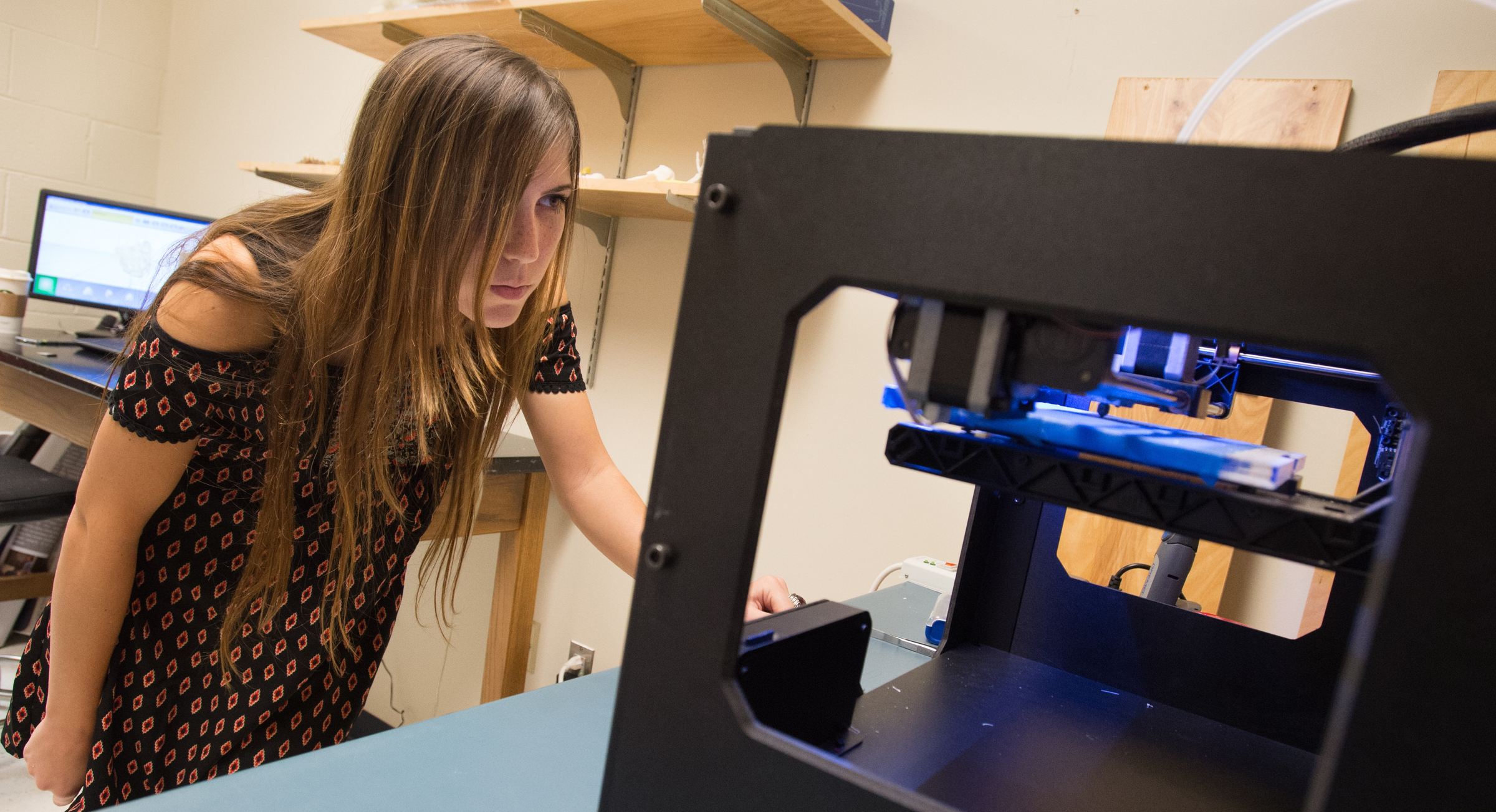

Killgrove, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of West Florida, gave students in her Human Osteology class a hands-on experience with prehistory by printing models of the bones from the Homo naledi species on a 3-D printer in the Division of Anthropology and Archaeology.

“I think it came out on a Thursday,” Killgrove said of the announcement of the new species. “I was able to download, print the models, bring them to class on Friday and ask, ‘Did you hear about the new species? Here it is.’”

Killgrove and Dr. Ramie Gougeon, also an assistant professor of anthropology at the University, have been using 3-D printing and scanning technology to recreate historical artifacts for the classroom – from the skull of a beaver to ancient ceramics.

The 3-D printing technology isn’t only being used to recreate bones and other artifacts at colleges and universities. It’s also being utilized in a host of industries, from producing automobile parts to developing medical devices.

Gougeon said he sees how his students’ ability to learn is enhanced when they are able to touch and examine 3-D digitized copies made of ancient projectile points, which are the stone tips that were attached to weapons such as arrows or spears.

Dr. Kristina Killgrove helps senior archeology major Melissa Poppy in her class.

Dr. Kristina Killgrove helps senior archeology major Melissa Poppy in her class.

“When you hand them the plastic version of it – even if it’s canary yellow – you see them turning it over, and you see them rubbing their fingers along it,” Gougeon said of the 3-D recreations. “It’s a totally different way of experiencing the artifact, and I think it’s a really valuable teaching tool.”

The 3-D printing in the Division of Anthropology and Archaeology will also be used to develop an app that will allow students to study the human skeleton, said Maddeline Voas, a biological anthropology graduate research assistant who is creating and printing 3-D models of skeletal materials and artifacts for research and teaching purposes this academic year.

“We’re 3-D printing one side of a human skeleton, and we’re going to make an app for students so they can go and modify it and learn more about it because not everybody has access (24 hours a day/7 days a week) to a skeletal collection,” Voas said.

Among the bones Voas is able to recreate in the lab is a sacrum with spina bifida, which takes about six hours to print. After the printing process is completed, Voas paints the skeletal materials or artifacts to add to the realism.

The 3-D printing and scanning technology will also allow the University to better develop a traveling archaeological exhibit for Gulf Power, Gougeon said.

“Obviously we can’t send that kind of stuff on the road without serious liability issues and the ethics of sending real artifacts out into the world,” Gougeon said. “But we can make really, really good replicas, and these can be viewed, they can be held. And it really allows for a number of different ways to teach the public and students about archaeology in a way that you just can’t do with one-of-a-kind artifacts or really fragile materials.”

With the 3-D printer, Killgrove has even been able to recreate bones that aren’t a part of the University’s collection. After putting a call out on Twitter for a copy of a hyoid bone – a horseshoe-shaped bone that supports the tongue – a British researcher who had scanned a hyoid from a an archaeological collection sent Killgrove the file, which she was able to download and print.

Dr. Kristina Killgrove uses some 3D printed artifacts in her class.

Dr. Kristina Killgrove uses some 3D printed artifacts in her class.

Killgrove said she hopes to use the 3-D technology to perform facial reconstruction of ancient Romans.

In terms of size, Killgrove said the largest item she’s scanned is a historic gravestone for the UWF Archaeology Institute.

“Over time, things had worn away, and we thought if we sort of scanned it with the fancy lasers we’d be able to read the inscription better,” Killgrove said. “And we were.”