Column: Middle-income families losing ground in Florida

Zach Jenkins, director of the Haas Center at the University of West Florida, shares his perspective on how middle-income families in Florida have fared since the 1970s.

By ZACH JENKINS | zjenkins@uwf.edu

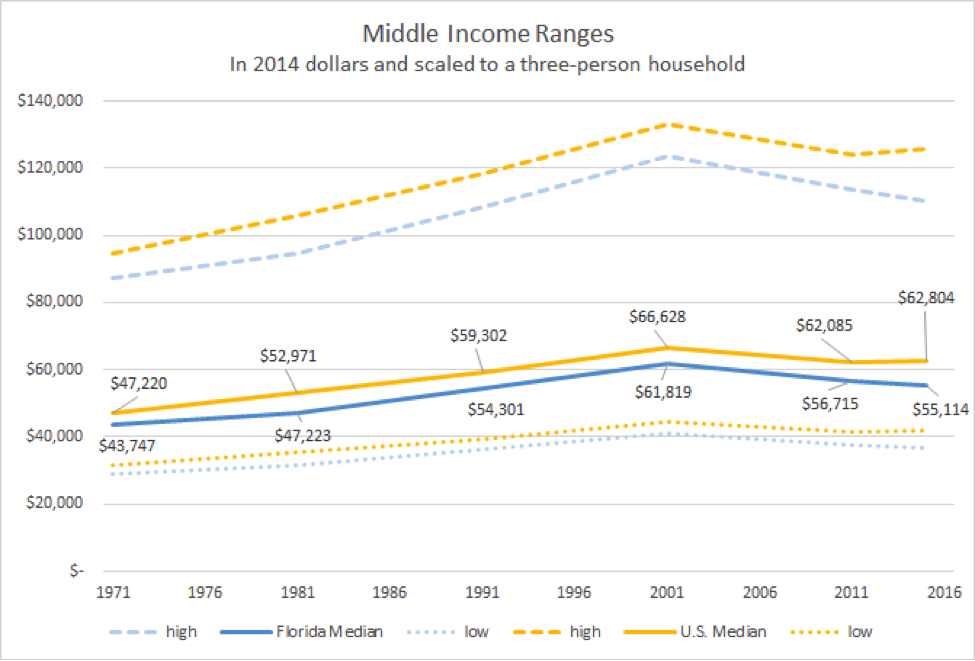

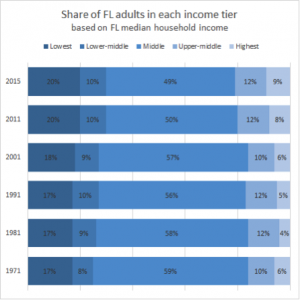

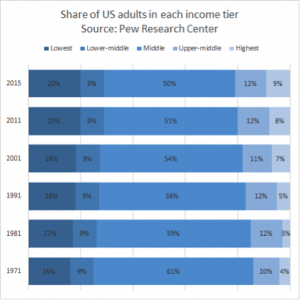

Last week, the Pew Research Center published a report documenting the shrinking “American middle class” from 61 percent of all Americans in 1971 to 50 percent today. Florida experienced an almost identical decline, but unlike the national trend, most of Florida’s lost middle class ended up in the lower-income tier. However, controlling for Florida’s median household income suggests that the movement out of the middle income tier is fairly balanced and corresponds to the polarization of Florida’s job market since the early 1980s.

The Pew researchers defined the “middle class” as American adults with a household income of between 67 percent and 200 percent of the median household income, as calculated from U.S. Census Bureau data from 1971 to 2015. Florida’s median household income is generally about 10 percent lower than the national median. As such, it is not surprising that the percentage of Floridians in the lower-income bracket was higher than in the U.S. as a whole.

The Haas Center used the same methodology and the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series International dataset to analyze Florida’s “middle class.”

While the percentage of middle-income adults dropped about 10 percent in both Florida and the U.S., there is a difference in where the 10 percent went. The Pew study indicates that the 11 percent reduction of the “middle class” since 1971 was favorably split – about 4 percent went to lower-income households and 7 percent went to higher-income households. Florida’s 10 percent reduction of the “middle class” is split in a less favorable way – about 7 percent went to lower-income households and only 3 percent went to higher-income households.

Further breakdown of the lower-income population reveals that the 7 percent shift into the lower-income bracket did not just creep into the “lower-middle” section, but instead skipped into the lowest-income households (i.e., those earning less than half of the U.S. median household income).

Florida’s “highest-income class” experienced very little growth since 1971. The 3 percent of Florida households who graduated from the “middle income” merely nudged into the “upper-middle” segment.

While this trend in Florida seems troubling, it is primarily a function of Florida’s lower household income. Florida’s workers are generally willing to work for a lower wage for a variety of reasons, including favorable taxes, moderate housing costs, lower cost of living, warm weather and proximity to beaches.

Using Florida’s median household income as a baseline instead of the national median, “Florida’s middle class” follows the same national trends in the Pew report. The middle-income tier lost the same 10 percent, but it was split more favorably – 5 percent was in the lower-income tiers and 5 percent was in higher-income tiers. It also reveals significant movement into the highest-income tier, which was not observed when applying the U.S. median household income figures.

The results are not surprising based on the increasing polarization of the job market since the early 1980s, as described in a 2013 report by University of Florida economists James Dewey and David Denslow. Wages and job demand are polarizing around analytical jobs (e.g., engineers, lawyers, accountants, etc.) and manual jobs (e.g., cooks, maintenance, transportation) with increasingly lower demand and wages for medium-skill routine jobs. Florida’s demand for manual jobs is outpacing the demand for high paying analytical jobs due to its large tourism industry and population of retirees. This pattern helps understand why Florida’s “middle class” has been moving slightly more to the lower-income tier as compared to the national figures reported by Pew.