Column: Affordable housing harder to find for local low-income families

Zach Jenkins directs the Haas Center at the University of West Florida in Pensacola, Florida.

By ZACH JENKINS | zjenkins@uwf.edu

For low-income families, affordable housing is not about their ability to purchase a home; it is about finding rent that is inexpensive enough so that they can still meet their family’s minimal food, clothing, transportation and medical care needs.

Unfortunately, the number of low-income households in Northwest Florida that are unable to find affordable rent has been steadily growing as rent has increased faster than median household income.

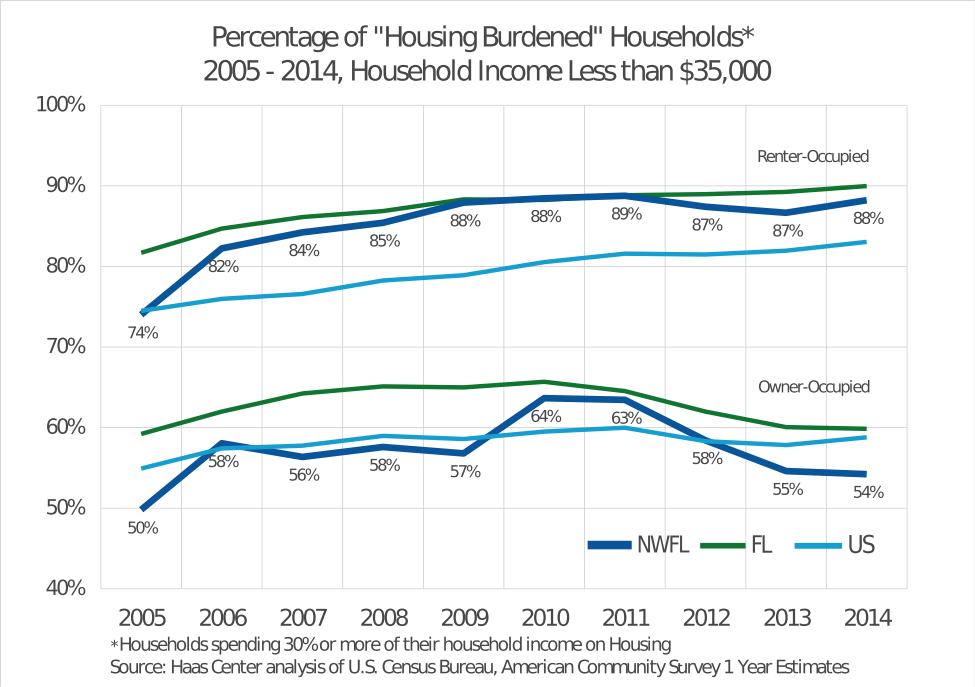

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development considers a family to be “housing cost burdened” if it spends more than 30 percent of its income on housing. Such “cost burdened” households are spending so much on housing that they may not be able to meet their other basic needs.

In 2005, the American Community Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, began publishing data indicating the percentage of households exceeding this 30 percent threshold, based on the household median income level. The Haas Center analyzed this data to compare Northwest Florida to the national and state trends.

For all three geographic regions, low-income homeowners are far less likely than low-income renters to spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. It was not surprising that the percentage of cost-burdened owner-occupied households would rise from 2005 to 2008 as home values and property taxes increased during the housing bubble. As property values and corresponding property taxes fell during the Great Recession, so did the percentage of owner-occupied cost burdened low-income households.

While it appears that the number of low-income homeowners experiencing housing burden is falling, the same is not true for low-income renters. The number of low-income housing-burdened renters in Northwest Florida has steadily grown from 74 percent in 2005 to 88 percent in 2014. The 14 percent increase in nine years is alarming, but perhaps not as alarming as the trend indicating the percentage might still be climbing.

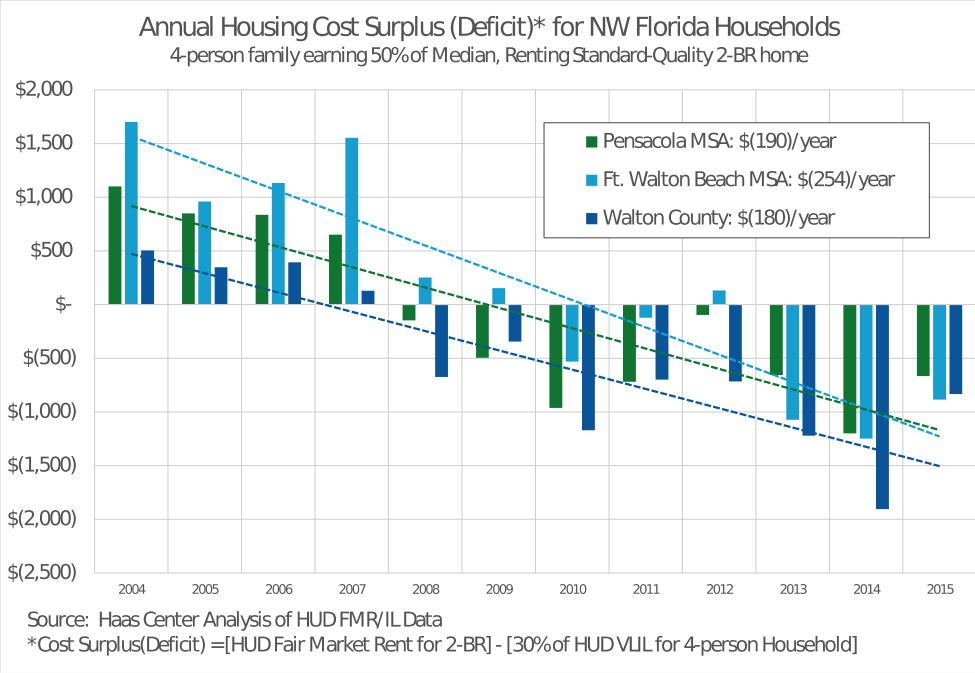

Each year, the HUD pulls from various datasets to calculate the “fair market rent” for rental property in thousands of counties, representing a rent estimate for “standard-quality rental housing.” It also calculates the median household income levels based on family size.

The HUD data can be used to describe the typical four-person, low-income family living in a two-bedroom “standard quality” rental in the Pensacola area. In 2004, this low-income family earned $2,113 per month, and its monthly housing costs for a modest two-bedroom were $542. Such a family’s housing would be considered affordable because their housing costs were less than $634 per month (i.e., 30 percent of their income).

By 2015, the narrative is different. A typical Pensacola four-person, low-income household in 2015 earned $2,575 per month, but the standard-quality two-bedroom cost $828 per month. An “affordable” rental would be $772. So this family would have to spend $54 per month more than it “should” spend on housing.

Since 2004, rental rates have been climbing faster than median household income in Northwest Florida. Using inflation-adjusted HUD data for the Pensacola area as an example, median income for a four-person household income actually fell by 3 percent from 2004 to 2015, while the fair market rent for a two-bedroom has grown by 22 percent over the same period. As a result, the Pensacola area low-income four-person household has been “losing” about $190 per year since 2004 as a result of climbing housing costs – money that should otherwise be spent on food, clothing, transportation and medical care.

Increasing demand for rental property since the Recession is the primary reason rental costs have been rising relative to household income. Many people who would otherwise be homeowners are forced to rent because their credit was ruined by a loan default. Likewise, stronger mortgage regulations passed since the Recession make it more difficult for borrowers to qualify for a mortgage, particularly those with high outstanding debt like student loans.

The status quo has the potential to create a cycle whereby renters cannot afford to save for a down payment for a home purchase because their rent is too high, thereby driving demand, and rent, even higher.