Two loves collide, leading history professor to UWF

Dr. Jamin Wells grew up in Rhode Island immersed in the maritime world. Alongside his father, who established one of the area's first police dive teams and later opened a dive shop, Wells began diving at age 10 in the cold, murky New England water and spent his youth spearfishing, racing sailboats and diving on shipwrecks. He worked as a dive instructor as an undergraduate and then paid for graduate school by dredging marinas and building docks.

Dr. Jamin Wells grew up in Rhode Island immersed in the maritime world. Alongside his father, who established one of the area’s first police dive teams and later opened a dive shop, Wells began diving at age 10 in the cold, murky New England water and spent his youth spearfishing, racing sailboats and diving on shipwrecks. He worked as a dive instructor as an undergraduate and then paid for graduate school by dredging marinas and building docks.

“I was on a tugboat at 2 a.m., reading about maritime history and cultural theory, while building marinas and doing really physical work,” said Wells, UWF Digital Humanities Lab director and assistant professor of history. “These two worlds I loved collided on that tug.”

Wells completed his undergraduate and graduate studies at the University of Rhode Island and expected to return to his hometown and work alongside his father, who by then had sold the dive shop and opened a mooring business.

“The job market is incredibly competitive in history,” Wells said. “I always felt I could go work for the family business or do other maritime careers. I didn’t go into my graduate programs thinking I had to get an academic job. I always thought I would be a really educated mooring guy back in Rhode Island.”

Instead, Wells headed to Cape Cod where he landed a position as an adjunct professor at Sea Education Association, a private, nonprofit educational organization that operates two sailing ships traveling throughout both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. He served as an adjunct while earning his doctorate at the University of Delaware as a fellow in the Hagley Program in Capitalism, Technology and Culture.

Wells learned about maritime history through his education and experience teaching at SEA and working in the family business, but he mastered how to actually apply that knowledge in the classroom when he taught at two high schools in New Orleans from 2013-15. Wells taught at schools on the opposite ends of the charter school spectrum—Miller-McCoy Academy, a struggling school where over 95% of the students qualified for free or reduced lunch that has since closed, and then New Orleans Military and Maritime Academy, a diverse and well-supported school.

“I was not really trained how to be a teacher in graduate school,” Wells said. “Becoming a certified teacher and then working in high-needs schools, I learned a lot of teaching techniques and strategies that I brought with me to UWF and use in my classrooms every day.”

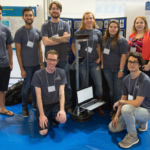

In January, Wells celebrated his fifth anniversary at UWF. He teaches courses in local, oral, digital and public history, along with overseeing the Digital Humanities Lab and the graduate program in Public History. He is just as proficient at motivating his students as teaching them.

“I’ve never met a student who didn’t like and respect Dr. Wells as a person and a professor,” said Melissa Williams, a history graduate student. “He takes the time to give detailed, specific feedback and goes above and beyond expectations to help his students be the best they can be. He recognizes the potential in everyone, and although they may hate him for it in the moment, he never lets them settle for anything less than their best, which students appreciate in the end.”

Geoffrey Ramirez, a history graduate student, said Wells blends traditional academic knowledge with real-world examples and experiences. He teaches beyond the textbook, using video games, music and guided tours as teaching tools.

“He designs his courses to maximize each student’s learning potential,” Ramirez said. “He ensures his students experience how classroom learning translates into the public sector. He understands our issues, our skills, our backgrounds and works his students at their level while still pushing them to improve.”

Faced with the same challenges as other professors of transitioning to remote instruction in 2020, Wells still managed to balance his teaching load with publishing his first book, “Shipwrecked,” launching the Gulf Coast Digital History Project and lending his expertise to a local nonprofit, Achieve Escambia, on an intensive ongoing study of Brownsville and West Pensacola.

“Shipwrecked: Coastal Disasters and the Making of the American Beach” delves into the history of beaches as they developed from isolated frontiers into thriving recreational spaces. Wells said shipwrecks changed how people thought about and experienced the beach during the nineteenth century in a way similar to how hurricanes and sea level rise are reshaping our experience with beaches today.

“The beach used to be feared,” Wells said. “It was seen as a hot, isolated, unproductive space, where you couldn’t grow anything—a really harsh environment. To make matters worse, every couple of years a big storm would inevitably come and do damage. People saving people from shipwrecks were the very foundation of the modern beaches we know today.”

While the book focuses on the northeast, exploration of the maritime history and heritage of the Gulf Coast is now readily available through the digital history project that Wells has overseen for the last three years. The collaborative project features an online portal hosted by UWF where one touch of a screen or click of a mouse allows users to explore thousands of digitized photographs, maps and other historic documents, along with a curated list of books and articles.

“This collection is a one-stop shop for students, scholars and researchers to delve into the rich maritime history of the Gulf Coast,” Wells said. “The collection is robust and we are working to further expand this resource.”

Some days Wells feels as if he is racing against the clock to complete his research and instruction while still spending quality time with his family. Yet, he manages to carve out a few hours each month for the Achieve Escambia partnership, where students are working on place-based projects to understand the intersection of race, policy and regional inequity.

His extraordinary work ethic resonates from those formative years performing backbreaking labor on the tugboat with blue-collar men who embraced the future professor as one of their own.

“I met a lot of interesting folks and heard some colorful language, but I learned a lot about honest work and making an honest living,” Wells said. “Those were some of the best years of my life…so far.”