UWF Researcher Studying DDT Levels in Escambia Bay, River

Pensacola – The pesticide DDT has been found in sediment samples from the Escambia River and its adjacent wetlands, a post-doctoral research associate at the University of West Florida has discovered.

Dr. Geoffrey Marchal, who was hired in April to begin the research, is now testing those sediment samples to see how readily available the pollutant is to the many diverse species that inhabit the bay.

“That’s the big concern,” Marchal said. “If the DDT in the sediment is bioavailable and can go through the food chain, then we have an issue.”

Since DDT and other pollutants can be held very tightly by the sediments, the optimal finding would be that the pollutant is stable in the sediment and out of the reach of wildlife, said Dr. Johan Liebens, a professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

“That’s not good, but it’s the best we can hope for in the current situation,” Liebens said of the possibility of that finding.

Marchal’s research is a follow-up to a study performed in 2009 by Liebens and Dr. Carl Mohrherr, who is now a retired professor from UWF. That study showed elevated levels of DDT in the sediments of the Escambia River wetlands that exceeded a Florida government guideline known as the probable effects level.

“We got the results back and they were really very high, at least in the wetlands, in the north end of the bay, not in the bay itself,” Liebens said. “In the bay itself, there was no DDT.”

However, some details of that initial study were difficult to explain, Liebens said.

DDT that has been present for a long time typically breaks down into its metabolites – DDD and DDE. But none of those breakdown products were present, Liebens said.

“It’s very, very unusual,” he said. “But one potential explanation was that the DDT was so recent, it didn’t have time to break down.”

And if the DDT has been used recently, it would be illegal. The U.S Environmental Protection Agency banned DDT in 1972 based on its potential hazardous environmental effects, including to wildlife as well as risks to humans.

The sediment samples from the study done by Liebens and Mohrherr, which was funded by the EPA, were taken to a private lab. Another possibility for the 2009 findings was that the lab was not able to detect the DDD and DDE breakdown products in the samples, Liebens said.

“Because it was very hard to explain the numbers that we got back from the lab, we wanted to go back and check and do the analysis in house,” Liebens said.

Marchal’s latest research, which was funded by a Scholarly and Creative Activities Committee grant from the UWF Office of Undergraduate Research, found that fewer sites contained DDT and the levels are lower than originally found in the 2009 study.

“The most important point is we found less sites with DDT,” Marchal said. “Originally, nearly all the wetlands were contaminated.”

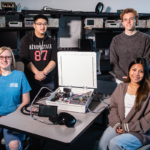

Marchal is still testing samples in the wetlands research laboratory at UWF. Liebens said he hopes that the findings of the study will be published in a scientific journal, possibly as soon as April.

Whether the researchers make any recommendations to government agencies depends on the results of Marchal’s testing, Liebens said.

“It depends on what we find with the bioavailability,” Liebens said. “If we would find really high levels of bioavailability then we could advise government agencies and draw their attention to what we have found.”