UWF Professor, Students Monitoring Shark Nursery Habitats

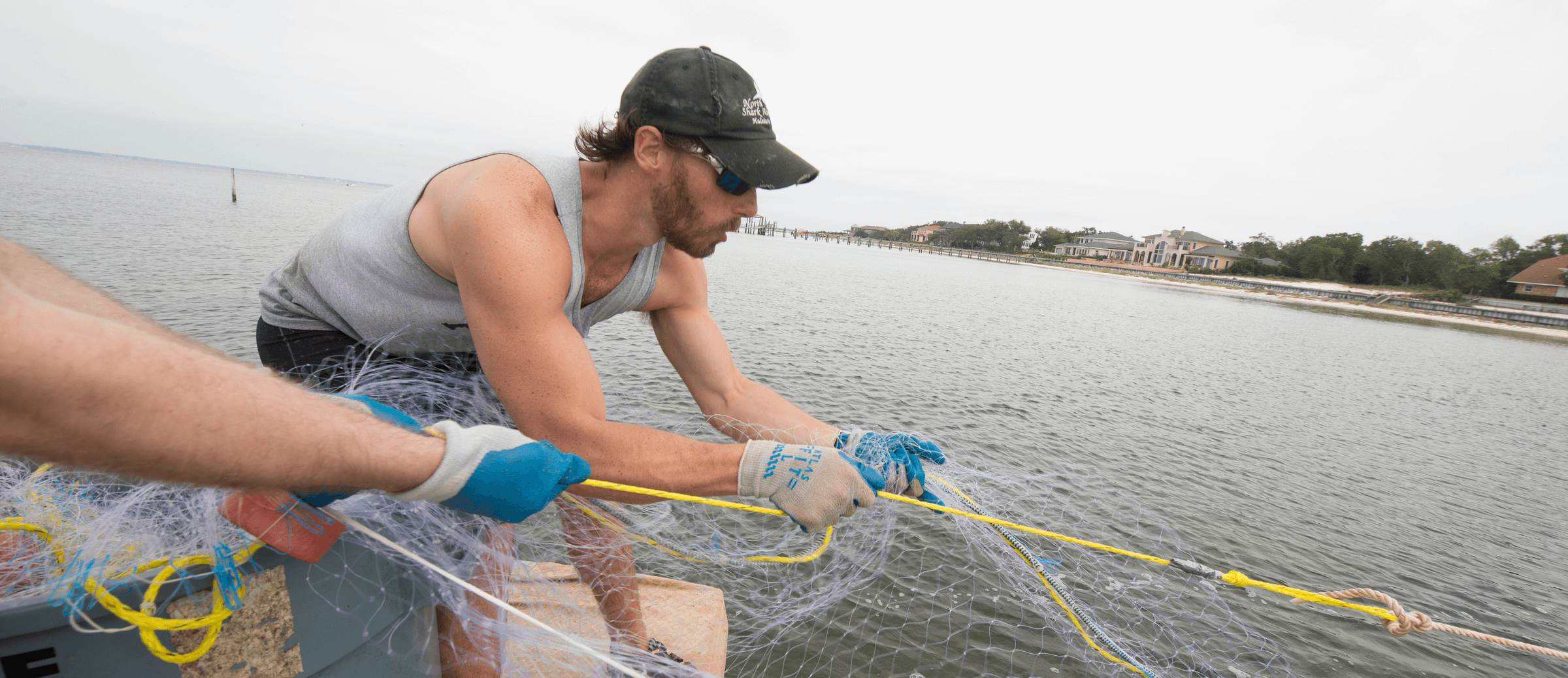

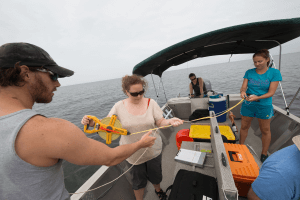

Pensacola – A crew of University of West Florida graduate students cast and set a gill net off a fishing boat in Pensacola Bay, hoping to catch a shark.

“We put it out there, and then we let it sit in the water for about 30 minutes, just to give the fish a chance to get in,” said Matt Davis, one of the graduate students on board.

It’s a process that the team, led by Dr. Toby Daly-Engel, an assistant professor in the Department of Biology, will repeat four more times throughout the day.

They were also hoping to net skates and rays, in addition to sharks, for crucial research and monitoring. What they haul back in during five stops throughout the bay are mostly catfish. No sharks.

The team’s research is part of the Gulf of Mexico Shark Pupping and Nursery project, which the Southeast Fisheries Science Center located in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Panama City laboratory has been conducting since 2003.

The goal of the program is to monitor the distribution and populations of sharks, skates and rays in the Gulf of Mexico in order to define and protect essential fish habitats, which are any habitats deemed critical to the survival of a species, mostly because they’re used for reproduction.

Daly-Engel has researched sharks for years, but until she arrived in Pensacola, no one studied the local predator populations. Her work has shown that the area seems to be a “giant dead zone” for sharks, she said.

“What I found is that it is incredibly underused by predators compared with Mobile Bay and Apalachicola and actually pretty much everywhere else that people are looking,” Daly-Engel said. “There’s just tons and tons of sharks, and, in Pensacola, there are very few. And when we do get sharks, they tend to be adults, not juveniles.”

While the reasons for the dearth of sharks in Pensacola are still being researched, Daly-Engel said it probably stems from a number of factors, including freshwater input into the bay and loss of critical habitat, such as seagrass.

Sharks develop slowly, taking on average 7-15 years to reach maturity, and have one of the lowest reproduction rates of any animal, Daly-Engel said. Most species spend their first few years in a nursery habitat, such as shallow bays and estuaries, where they’re safer from being eaten by larger sharks. The juvenile sharks can also find small prey there.

Because of their slow growth, many shark species in the Gulf of Mexico have trouble recovering after an environmental disturbance such as an oil spill. Pollution and overfishing have put populations of some sharks, such as hammerheads, on the verge of extinction, she said.

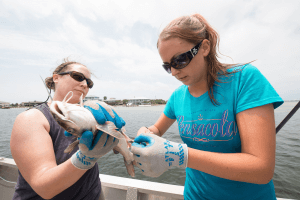

UWF graduate student Cody Nash takes a catfish fin sample which will be put in vials of nontoxic preservative and taken to the lab for genetic testing.

UWF graduate student Cody Nash takes a catfish fin sample which will be put in vials of nontoxic preservative and taken to the lab for genetic testing.

“We know that the Gulf of Mexico has been impacted in certain ways. And so, if the populations of sharks here take a hit, is there a source somewhere where they’re going to be coming in from to rebuild those populations? Or, once they’re gone, are they just gone?” Daly-Engel said.

While looking for sharks, which when caught will be tagged and released, Daly-Engel and her students also perform other important biomonitoring when out on the water. For example, tissue samples are taken from the catfish that are caught, which are then put in vials of nontoxic preservative that will be brought to a lab for genetic testing.

Even though the UWF crew didn’t catch any sharks on their recent outing, a fisherman in a kayak brought them a Southern stingray he caught using shrimp. The team then took a tissue sample from the stingray.

Each graduate student on board is also working on thesis projects involving sharks. For his thesis, Davis is studying the genetic stock structure of the Atlantic sharpnose shark.

“It gets about a meter along, and it makes up about 46 percent of sharks caught in the Gulf of Mexico every year,” he said.

Daly-Engel said once researchers understand which habitats and conditions are most important for baby sharks to thrive, they’ll have a better idea how to help the populations rebound, which will boost the health of the marine ecosystem.

“We know sharks like to use bays to reproduce in, and a healthy bay is one that has a lot of baby sharks,” Daly-Engel said.