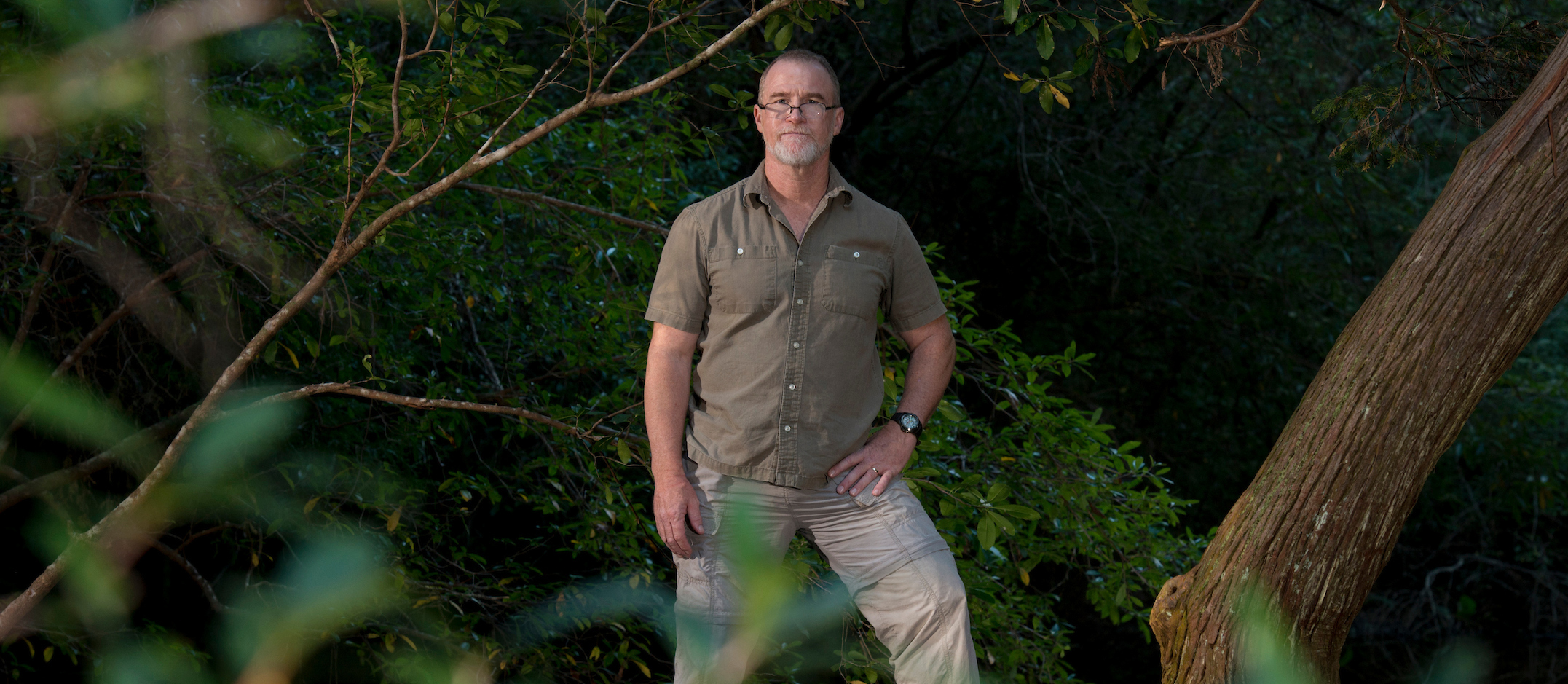

UWF Professor Studies Apple Snail, Endangered Snail Kites

Pensacola – Typically growing to be larger than a golf ball, the apple snail is the meaty meal of choice for predators such as alligators, turtles and fish.

However, no species is more dependent on the apple snail than the snail kite, a hawk-like bird of prey found throughout Central and South Florida.

“It’s 99 point something percent of their diet,” said Dr. Philip Darby, a biology professor at the University of West Florida. “It’s all they eat.”

For more than 20 years, Darby has researched both apple snail and snail kite ecology, sampling the wetlands they inhabit from Orlando to the Everglades. Snail kite numbers dwindled significantly over that period. Darby has data that indicates much of that decline can be attributed to the loss of habitat quality and the scarcity of apple snails, its main food source.

“We observed a decline in snail kites starting about 1998,” Darby said of the federally and state listed endangered species. “There used to be, the estimate was about 3,000. And now we’re down to about a 1,000.”

Darby recently wrapped up a study funded by a four-year grant from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The problem for the snail kites is not so much the number of apple snails overall, but that they’re so thinly spread and low in density that the kites can’t find them fast enough to keep up with their dietary needs. Darby uses the scale of a football field to describe the snail kite’s dilemma with finding snails.

“If you have a football field and you have 10,000 snails in it, or say 5,000 snails, that’s probably about right for supporting the snail kite. But if you get down to say around 100 snails in that football-size area, it’s not near enough, and the kite will try to forage there and then leave,” he said. “The density, the number of snails per area is important. And what we’ve noticed, where the kites have abandoned certain wetlands, including major portions of the Everglades – they are hardly there anymore – it’s because of those low snail densities.” Darby also documented a crash in the apple snail population in the Everglades and other wetlands.

The largest freshwater snail in North America, the apple snail only lives about a year to a year and a half and there have to be “fairly constant” suitable conditions that allow them to persist, Darby said.

One of the main issues hampering their ability to thrive is that crucial wetlands are drying up.

“We have found out that some of the areas where we no longer have apple snails where we know they were before, it’s drying out too frequently,” Darby said. “In other areas, and this is more recent, where water levels are too deep, that can cause problems for snails, too. It doesn’t kill them outright and they may still have some reproduction, but the reproduction is at much lower rates.”

It’s estimated that 50 percent of wetlands in South Florida have been drained, Darby said.

“So if you drain the wetlands, you lose the snails, you lose kite habitat,” Darby said. “The most likely explanation for the original decline in snail kites is just habitat loss. But what we’ve documented since the 1990s, is that apple snail populations have gone down in some of the wetlands that are still there.”

Darby’s research is designed to help natural resource managers such as U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, South Florida Water Management District and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in their decision making, including what water depths are needed that are most suited for apple snail reproduction and survival.

“My job is to explain what we think regulates snail populations,” Darby said. “The folks that do all the engineering, the hydrologists and the biologists that look at other things, have to factor in my information along with everything else.”

While the restoration of the Everglades is a “good thing,” there are some potential negative impacts on kites, depending on where the water is going to flow and how deep it is, Darby said.

“There are a number of regulations tied to changes in water management. Most of the waterways in Central and South Florida are controlled through water control structures and canals and levees,” Darby said. “They need to know where and for how long to pull the plug on certain wetlands or to let water flow into certain wetlands. If there is water in the system they can lower the water levels, or sometimes, for example on Lake Okeechobee, you can bring water and move it down through the Everglades.”

Bethany Wight, who graduated from UWF with a master’s degree in 2013, helped Darby sample the snail population in the Everglades. Her master’s thesis focused on the abundance and distribution of apple snails within different habitats and the movements of the snail kite. She now works as a research biologist at the University of Florida’s Rangeland Cattle Research and Education Center.

“The field work, it helped me be a problem solver in more real-life situations that I encounter now,” Wight said. “I did a lot of data analysis, management and writing that was external from my thesis that Dr. Darby exposed me to and that’s given me a good set of tools all around for going into the real world and actually applying it to a job.”