UWF Professor Finds Rare Sturgeon Using Environmental DNA

The Alabama sturgeon is critically endangered, so much so that some believed the species had become extinct.

The last documented capture of the freshwater fish was on April 3, 2007, on the Alabama River by biologists with the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. An Alabama sturgeon was last spotted near Robert F. Henry Lock and Dam on April 23, 2009, but it was not netted.

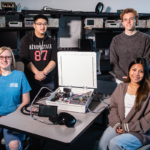

However, recent research led by Dr. Alexis Janosik, an assistant professor in the Department of Biology at the University of West Florida, has discovered that though the Alabama sturgeon may have dwindled greatly in numbers, it’s not extinct.

Using the science of environmental DNA, Janosik has found evidence that the sturgeon still dwells in the Alabama River.

Water samples were taken from the Alabama River in the state’s southwestern region, which were then taken back to the lab to filter to try to find the Alabama sturgeon’s DNA from scales, feces, urine, gametes – any trace the fish might leave behind.

In December 2014, 30 water samples were collected near and throughout the Alabama River and one of those samples tested positive for the Alabama sturgeon. From April to July 2015, another 100 water samples were collected, and 17 of those samples tested positive for the critically endangered fish.

Janosik said the main goal of the research was to promote conservation efforts to help preserve the Alabama sturgeon.

“This helps inform people to say, ‘It’s still there. This isn’t lost. We still have to make an effort,’” Janosik said.

Janosik’s research is slated to be published in Global Ecology and Conservation, a peer-reviewed, open-access journal.

The research project is being funded by the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and Janosik collaborated with Mariah Pfleger, former UWF graduate student, Dr. Carol Johnston, a professor at Auburn University, and Steve Rider, river and stream fishes program coordinator with the Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries.

Several factors have caused the Alabama sturgeon’s numbers to shrink, Rider said.

“They were overfished. And then once the dams came in, that was kind of the nail in the coffin for these fish,” Rider said, after accompanying Janosik and one of her students on one of their trips to collect water samples.

The Alabama sturgeon takes a long time to reach sexual maturity and doesn’t reproduce every year, Janosik said.

“There are many things about this fish that make it a poor candidate for harvesting, yet it was overharvested, which ultimately led to its current status – in addition to environmental degradation, river impoundments, and a complicated life history strategy,” Janosik said. “All these things together are compounding.”

The use of eDNA tells officials with the Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries where in the river they need to search to try to collect the sturgeon, Rider said.

“One of the things behind his project is trying to collect enough sturgeon so we can establish a brood stock for restoration,” Rider said.

In addition to finding traces of the Alabama sturgeon, water samples collected during the research also found ample evidence of the Gulf sturgeon, which, while not as rare as the Alabama sturgeon, is listed as a federally threatened species.

Species such as mooneye fish, Alabama shad and freckle belly madtom, will also be searched for using eDNA, Janosik said. The technology will also be used to determine if lionfish, an invasive species that is already prevalent in the Gulf of Mexico, are moving into local river systems.

“This tool saves us time, saves us money, energy, resources and can still inform conservation management,” Janosik said of eDNA.