Oil Spill-Related Research Dollars Drive New Understanding of Gulf

Pensacola – In 1989, the California-bound Exxon Valdez oil tanker struck a reef in Prince William Sound and over several days dumped the largest volume of oil ever released into U.S. waters.

It was a record that stood until 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded and sank in the Gulf of Mexico, gushing British Petroleum oil from the sea floor for 87 days.

Founded in 1990, the University of West Florida’s Center for Environmental Diagnostics and Bioremediation was well positioned to respond to calls for intensified marine research in the Gulf of Mexico following the catastrophic BP spill.

“When the CEDB was created, it was largely in response to the Exxon Valdez oil spill,” said Wade H. Jeffrey, director of the CEDB and professor in UWF’s Department of Biology. The CEDB boasts five research laboratories and is located on UWF’s main campus.

“We have been involved in marine research since the inception of our center,” Jeffrey said. “We’ve worked up in the estuaries and what we call blue-water oceanography in a wide variety of marine environments.”

So when the Deepwater Horizon spill occurred, the CEDB was ready with expertise, facilities and equipment.

“We’re local,” Jeffrey said. “The spill was right in our backyard.”

BP committed to pay $500 million over 10 years to support independent research through the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). BP reports that GoMRI has so far awarded about $315 million in grants for research that will “improve society’s ability to understand, respond to and mitigate the potential impacts of oil spills to marine and coastal ecosystems.”

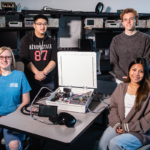

GoMRI reports that 60 UWF researchers – including faculty and staff members and students – have been involved out of a total 2,862 researchers from 246 institutions. The consortia offers scientists an opportunity to collaborate with their peers not only throughout the Gulf Coast, but also throughout the world, Jeffrey said, and to “train a big collection of graduate and undergraduate students, providing hands-on and real-world research and other opportunities.”

The CEDB currently is involved in two of the eight original GoMRI-funded research consortia:

- Deepsea to Coast Connectivity in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico (DEEP-C), studying the environmental consequences of petroleum hydrocarbon release in the deep Gulf on living marine resources and ecosystem health.

- Center for the Integrated Modeling and Analysis of Gulf Ecosystems II (C-IMAGE II), to advance understanding of the processes and mechanisms involved in marine blowouts and their environmental consequences. The CEDB recently was awarded a $231,000 GoMRI grant for continued and expanded C-IMAGE II research.

Another significant source of research money for the Gulf is through the Resources and Ecosystems Sustainability, Tourist Opportunities, and Revived Economies of the Gulf Coast States (RESTORE) Act of 2012. The RESTORE Act created a Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund which will receive 80 percent of any Clean Water Act civic and administrative penalties paid by BP and other companies responsible for the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The fund supports a variety of restoration, recovery and research activities in the Gulf.

CEDB professor Jane M. Caffrey hopes to tap into RESTORE money to fund several projects and initiatives.

“We’re trying to jumpstart a new center on campus – the Gulf Islands Research and Education Center, a partnership between the National Parks Service and UWF,” Caffrey said.

A grant proposal seeks RESTORE funding to do environmental monitoring in the Santa Rosa Sound and identify sea grass beds that are at risk. If funded, the program would provide more educational opportunities for students and also seek citizen volunteers from organizations such as the Bream Fishermen’s Association.

BP oil workers attempt to clean oil covered sand on June 23, 2010 in Pensacola Beach.

BP oil workers attempt to clean oil covered sand on June 23, 2010 in Pensacola Beach.

Even for research projects not directly tied to the Deepwater Horizon spill, there is an oil nexus.

“The oil spill has an impact on what I’m studying,” Caffrey said. “I’m particularly interested in how oysters may be able to remove excess nitrogen and improve water quality.”

Caffrey said RESTORE funding is being sought to answer the question.

“If oysters are exposed to oil hydrocarbons, will that affect their ability to clean the water?” she said.

Another research project underway is “near and dear to every fisherman’s heart,” Caffrey said.

“We are trying to do some experimental research tying into early RESTORE money Escambia County has already gotten to establish some artificial reefs,” Caffrey said.

She and Will Patterson, an artificial reefs expert at Alabama’s Dauphin Island Sea Lab, are partnering with Escambia County to look at what happens when an artificial reef is installed and how it influences the fishing community.

“We want to know if artificial reefs lead to increased fish production, or do they just bring them in from other areas and concentrate them into that area?” Caffrey said.

“The implications from our research would be extremely valuable to (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration),” she added. NOAA assesses and predicts the status of fish stocks.

NOAA’s methods for counting reef fish, such as red snapper, have recently come under fire from Gulf Coast businesses and government leaders unhappy with short red snapper seasons and catch limits.

While the Deepwater Horizon explosion and spill was certainly a nightmare scenario, the ensuing wave of research funding has been a scientist’s dream come true.

Katelyn Houghton is a recent UWF graduate now serving as an Oak Ridge Institute for Science Education intern at the Environmental Protection Agency on Pensacola Beach.

“I work here on projects pretty similar to what we did at UWF,” Houghton said. “Due to the influx of all the grants, I think that research is going to increase in the Gulf and we’re going to really have an understanding of all the processes involved in the ecosystem response to the oil spill.”

An investment into Gulf of Mexico research was long overdue.

“Prior to the spill, the Gulf was not well characterized or understood,” CEDB Director Jeffrey said, adding that before the spill, the Gulf of Mexico typically got short shrift when it came to research funding.

Validating his point was a presentation made a year before the BP spill, when the Gulf States Governors Alliance reported that even though the Gulf of Mexico represents the seventh-largest economy in the world, it annually received only a fraction of the funding directed to the Great Lakes and Chesapeake Bay.

“Understanding the Gulf of Mexico as an ecosystem is imperative to understanding not only what happened in the Deepwater Horizon spill, but also in future events,” Jeffrey said. “A lot of people took it for granted – they thought it was a big ocean and you can do what you want. But it only took one event to cripple the economy of the Gulf of Mexico.

“Now we have had an infusion of research into the Gulf of Mexico to understand it, what it can and cannot do and how it works,” Jeffrey said. “The silver lining is that now people appreciate the Gulf of Mexico in ways they never did.”

Written by Martha Simmons