Is Northwest Florida Heading for Another Housing Bubble?

Back in 2005, the National Association of Realtors produced the report “Home Price Analysis for Pensacola-Ferry Pass-Brent” in which the author found the local metropolitan housing market to be in “excellent shape” with potential for significant equity gains.

The report analyzed median mortgage servicing costs and median incomes ratio and found that for Escambia and Santa Rosa counties, “This ratio is at a very manageable level. It implies no widespread financial overstretching to purchase a home in the region. Any respectable gains in the local job market could translate into further home price gains.”

Other significant findings in the report included that price declines in the local market were unlikely and the local market would experience a 5 percent decline only under extremely unlikely scenarios of much higher mortgage rates.

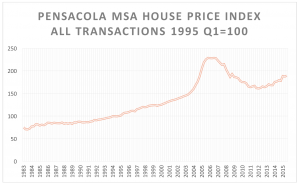

Sadly, those words were not prophetic. The quarterly House Price Index generated by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis is charted below and clearly shows that Pensacola shared in the pain of the housing market collapse.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED Economic Data and Florida Department of Economic Opportunity QCEW data.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED Economic Data and Florida Department of Economic Opportunity QCEW data.

The index includes all transactions in an area using both sales prices and appraisals. Between the height of the market in the fourth quarter of 2006 to its lowest point in the second quarter of 2012, house prices fell 29.4 percent in the Pensacola area.

In addition to clearly showing the run-up in prices that began in 2003, the chart also shows that the area is just now recovering to 2005 price levels. While prices have rebounded 17.5 percent from their lowest point as of the last quarter of 2015, as illustrated by the trend line, they are still below what might be expected if the bubble had not happened.

Now, just 10 years removed from the height of the housing bubble, there are whispers that another bubble is forming. Housing prices in many areas are once again rising at rates faster than average wage growth, credit conditions are loosening with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac allowing only 3 percent down payments, and housing supplies are tightening. Are we headed for a repeat of the last disaster?

To answer this question, one first needs a definition of “housing bubble.” It’s typically defined as a deviation of the market price from the fundamental value of the house.

Secondly, one needs to be able to tell if this deviation is occurring. This would seem to be a straightforward task. However, like many things in the economic world, there is more than one way to analyze the question, and experts don’t always agree on what these analyses show.

For example, one researcher might point to home prices increasing at a higher rate than inflation, coupled with a sharp divergence between home prices and rental prices, as an indication that homes are overpriced. Another will examine the ratio between housing price and income and, having noted that it is higher than historical norms, might conclude that there is a price bubble. Still another researcher will look at mortgage-servicing costs as related to income, and argue that if these are within manageable levels, there is no bubble.

The current consensus amongst experts seem to be that while housing prices are climbing, they are doing so because new houses are not being built to increase the supply. Identified as a major indicator of the prior bubble, new homes were being built at a furious pace even as prices continued to climb. Under normal economic conditions, prices tend to fall when supply grows. When that does not occur, it suggests that other forces are in play to support the higher price.

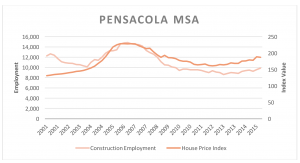

While housing starts are not readily available for metro areas, a proxy for specific new home construction statistics is employment in the construction industry itself. By comparing home prices to the number of construction workers, one can see how these forces might interact. The chart shows the house price index as compared to quarterly construction employment in the Pensacola area from 2001 through the third quarter of 2015.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED Economic Data and Florida Department of Economic Opportunity QCEW data.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED Economic Data and Florida Department of Economic Opportunity QCEW data.

The data show construction employment at its height during the price bubble and lagging behind prices ever since. This fact suggests that experts may be correct in their view that conditions are still operating in a traditional fashion and a lack of housing supply is supporting home prices at present levels rather than the factors that generate bubbles. Building permit data from the U.S. Census Bureau tends to support this notion as well – at the height of the bubble in 2006 the Pensacola area saw 2,488 permits issued covering 3,126 housing units. By 2012, the number had dropped to 1,466 permits covering only 1,594 units – or half the planned construction.

The most recent data does show housing starts and construction employment on the increase. It will be interesting to watch how these trends play out in the coming months.

Phyllis K. Pooley serves as director of special projects with the University of West Florida Office of Economic Development and Engagement in Pensacola.