Health Care, Other Benefits Becoming More Costly to Employers

Ever wonder why your employer says they can’t afford to pay you a higher wage? For some, it could be the rising cost of fringe benefits.

In addition to the expense of recruiting new workers, physical space, equipment and training, non-wage costs for employees at a minimum include legally required benefits such as Social Security and workers’ compensation insurance. They also often also include health insurance, paid leave and retirement plans. Over time, these fringe benefit packages have grown to represent a larger and larger share of an employer’s total cost per employee.

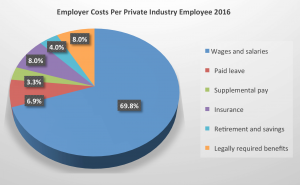

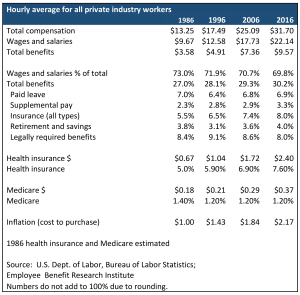

These labor costs are tracked by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Its Employer Costs for Employee Compensation product is a quarterly report that, using National Compensation Survey data, shows employers’ average hourly cost for total compensation and its components. Key features from the report include showing compensation costs both as a dollar amount total and broken out by wages and salaries and total benefit costs. Total benefit costs are further separated into benefit costs for broad benefit categories, such as paid leave, supplemental pay, insurance, retirement and savings, and legally required benefits. Costs are further drilled down into detailed benefits, such as paid holidays, health insurance, defined benefit pension and workers’ compensation. The chart illustrates the breakout of average employer costs in 2016 for private industry employers using the most recent ECEC data.

While wages still make up the lion’s share of employer costs, non-wage costs now represent over 30 percent of the total employee cost. And as the trend table (below) indicates, the non-wage portion of employer costs has been steadily increasing since the mid 1980s.

While wages still make up the lion’s share of employer costs, non-wage costs now represent over 30 percent of the total employee cost. And as the trend table (below) indicates, the non-wage portion of employer costs has been steadily increasing since the mid 1980s.

Insurance costs represent by far the largest increase in employer costs since 1986. And by far the biggest component of these insurance costs is health care. While representing 5 percent of total employer costs in 1986, non-Medicare health care costs have increased to 7.6 percent of total employer costs per employee in 2016. Healthcare costs during the time rose significantly faster than general price inflation.

Insurance costs represent by far the largest increase in employer costs since 1986. And by far the biggest component of these insurance costs is health care. While representing 5 percent of total employer costs in 1986, non-Medicare health care costs have increased to 7.6 percent of total employer costs per employee in 2016. Healthcare costs during the time rose significantly faster than general price inflation.

Between 1986 and 2016, inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index increased the price of items that cost $1 in 1986 to $2.17 in 2016 – an increase in prices of 117 percent. At the same time, the price of providing medical benefits to employees increased from approximately 67 cents to $2.40; a cost increase of 258 percent for an inflation rate of over double that of other items. As a comparison, wages and salaries only slightly outpaced inflation during the 1986 to 2016 time period, with an average increase of 129 percent. As non-wage employer costs continue to rise, employers and employees are both faced with tough choices. In order to remain competitive, employers may be forced to reduce benefits to avoid passing too many costs onto consumers. This could cost them valuable workers.

Conversely, employees wanting to retain current levels of benefits may not see salary increases as employers instead must use revenues to fund these benefits, or even pass more of these costs onto workers. This could cost employees financial stability as they fall behind in the ability to save. Many of these results have been and are still being seen in the current economy.

If non-wage employer costs continue to represent a larger share of the compensation pie, both employers and government regulators will need to take a hard look at these costs. While legislation such as the Affordable Care Act was intended to address a major cost driver for employers, its impacts may not have fully made it into the data as yet. While the data do reflect that the rate of increase in health care costs as a fringe benefit have slowed, these costs are still significantly outstripping the general inflation rate.

Phyllis K. Pooley serves as director of special projects with the University of West Florida Office of Economic Development and Engagement in Pensacola.