Concentrated Poverty Less Severe in Escambia than Nation

For poor families, neighborhood poverty can be as much of a hindrance as their own lack of income. According to recent Census data, a growing number of Escambia County residents earning below the poverty line are converging into a few neighborhoods, creating pockets of high-density poverty.

While the growth of concentrated poverty has been slower than the national average, the presence of neighborhoods of concentrated poverty has been shown to have adverse effects on not just the poor, but even those above the poverty line throughout the community.

To study such neighborhood poverty effects, the U.S. Office of Housing and Urban Development commissioned a 10-year research demonstration in which it randomly selected a few thousand families living in neighborhoods of high-density poverty and enabled them to move into less-poor areas. The data from this “Moving to Opportunity” study has shown that those who moved from poor areas into less poor areas experienced improved mental and physical health, including lower rates of obesity, stress and diabetes. For children who moved from a high-poverty neighborhood before age 13, researchers found improved long-term educational and occupational outcomes.

The Brookings Institution recently reported on poverty concentration trends for the nation and the largest 100 cities. A neighborhood of concentrated or extreme poverty is one in which more than 40 percent of a census tract’s population lives below the poverty line. The Brookings study of the 2010-14 five-year American Consumer Survey data revealed that 4.4 percent of Americans and 13.5 percent of our poor live in communities with concentrated poverty. This is an increase of 3 percentage points since 2005-09.

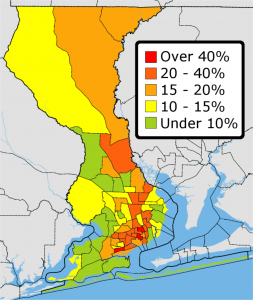

The Haas Center used the same methodology to study concentrated poverty within Escambia County. Using the Brookings study terminology, 3 out of Escambia County’s 71 neighborhoods are considered “extremely poor,” and another 19 would be considered “high poverty.” Escambia has significantly lower rates of concentrated poverty than the nation as a whole with only 2.7 percent of its residents – 7.2 percent of its poor – in concentrated poverty, which is only 0.5 percentage points higher than 2005-09.

Similar to the national trends, the population growth in Escambia’s extremely poor neighborhoods is not uniform among its demographics. For the 2010-14 period, black residents were 22 percent of the total population of Escambia County. However, black residents represent 40 percent of Escambia’s poor and 80 percent of the concentrated poverty population.

During the same period, white non-Hispanic individuals were 67 percent of Escambia’s population, 45 percent of its poor, but only 8 percent of the population living in dense poverty.

From 2005-09 to 2010-14, the share of poor white residents living in concentrated poverty fell by 2.5 percentage points, while the share of black residents in extremely poor communities increased by 3.4 percentage points.

The Hispanic population has grown by 52.1 percent from 2005-09 to 2010-14 and is now 4.7 percent of the total population of Escambia County. However, the share of persons of Hispanic ethnicity within the poorest communities has grown by 4.6 percentage points, which is the highest growth of any racial or ethnic group.

Zach Jenkins is the director of the Haas Center at the University of West Florida in Pensacola.